Key Takeaways

- Labor force participation among people with disabilities has significantly increased since the start of the pandemic.

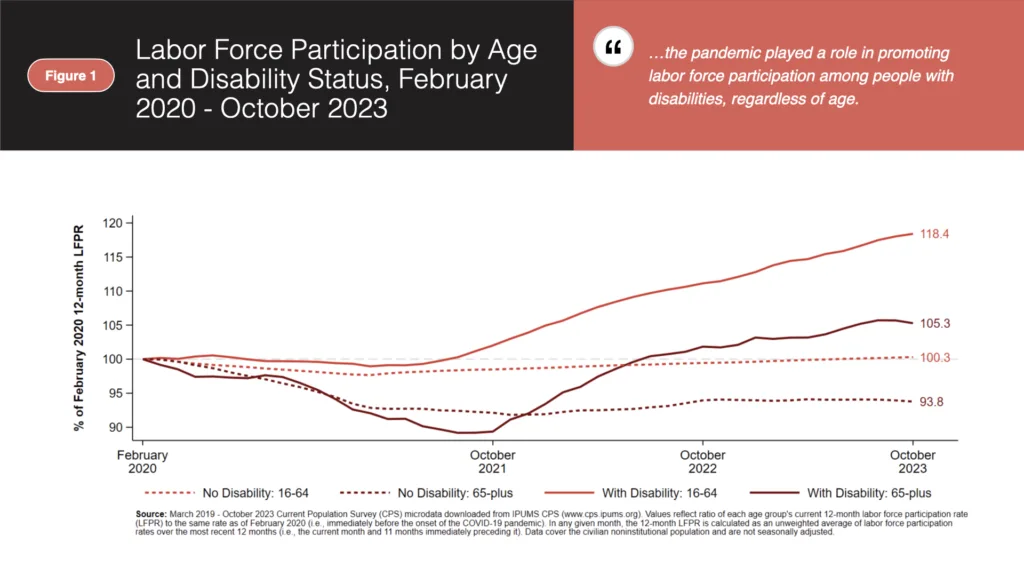

- In October 2023, the average labor force participation rates for people with disabilities ages 16-64 and 65-plus stood at 118.4 percent and 105.3 percent (respectively) of their February 2020 values.

- The expansion of remote work opportunities, which facilitate employment for people with disabilities who face barriers to working away from home, is at least partially responsible for these trends.

- These findings highlight a pressing need to proactively challenge our assumptions about the nature of work and develop labor policies and employment practices that meet the needs of all workers, regardless of age or ability.

Falling labor force participation – particularly among older adults – has fueled headlines in countless news stories since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020. However, a closer look at the data reveals a more complicated story, including rapidly rising labor force participation among people with disabilities, regardless of age. Recognizing this trend and understanding its implications for the future of work is critical to developing labor policies and employment practices that increase labor market access and maximize opportunity for people of every generation.

To understand how COVID-19 has affected the American civilian labor market,1 it is useful to examine the 12-month labor force participation rate (LFPR) for any group as a percentage of its value in February 2020 (i.e., immediately before the pandemic).2 Among people ages 16-64 without a disability,3 monthly labor force participation declined dramatically in Spring 2020 but recovered quickly thereafter;4 as a result, the 12-month LFPR of this group never fell below 97.7 percent of its February 2020 value and returned to pre-pandemic levels by the middle of 2023.5 Conversely, the decline in average labor force participation among adults age 65-plus without a disability has been sharp and sustained, so that the 12-month LFPR of this population in October 2023 was just 93.8 percent of its pre-pandemic value. This decline represents hundreds of thousands of lost labor force participants and has significantly contributed to an ongoing labor shortage in the United States.

Average labor force participation among people with disabilities evolved very differently over the same period. Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, the 12-month LFPR for people with disabilities ages 16-64 never fell below 98.9 percent of its February 2020 level. Instead, it has risen rapidly since the middle of 2021 and reached 118.4 percent of its February 2020 value by October 2023. The 12-month LFPR for people with disabilities age 65-plus did decline significantly during the first 18 months of the pandemic, falling as low as 89.2 percent of its February 2020 value in August 2021. However, it has experienced a strong resurgence since then and stood at 105.3 percent of its February 2020 level as of October 2023.

These findings strongly suggest that the pandemic played a role in promoting labor force participation among people with disabilities, regardless of age. The 12-month LFPRs for people with disabilities ages 16-64 and 65-plus in October 2023 (40.2 percent and 8.6 percent, respectively) are at or near historic highs,6 and current trends indicate that both rates will continue to rise over time. Although several factors may be responsible for this increase in labor force participation, two key drivers are the sudden abundance of opportunities for remote work and widespread access to the technological innovations that make remote work possible (e.g., video conferencing services that offer features such as closed captioning for conference calls).7

There is an important lesson in these findings: Costly barriers to employment may stem from entrenched attitudes about the nature of work. Remote work existed before the pandemic but was viewed as a niche arrangement for a handful of specific skill sets. When remote work became unavoidable due to lockdown measures and social distancing, policymakers and employers quickly realized that a broad segment of the workforce could function productively from home, even after the pandemic subsided. This shift in perception has expanded employment opportunities for millions of people with disabilities and benefited thousands of employers facing a historic labor shortage.

The analysis above highlights the value of proactively challenging assumptions about the nature of work, including labor policies and employment practices that implicitly or explicitly promote ableism and prevent people with disabilities from working.8 Given that older adults are far more likely to have a disability relative to the general population, AARP has pioneered innovative solutions in this area for many years. One example is AARP’s Senior Community Service Employment Program, which helps low-income, unemployed individuals age 55-plus find work. Relatedly, the AARP Job Board includes features that help job seekers with disabilities identify compatible employment opportunities, and AARP Skills Builder for WorkSM provides resources for developing skills that are competitive in the job market and aligned with one’s specific needs. Finally, AARP Foundation’s legal advocacy work often targets ADA violations and other barriers that impact workers who have a disability. Efforts such as these improve labor market conditions for workers with a disability and employers, producing economic gains benefiting every generation.

- Due to the design of the Current Population Survey (CPS), all analysis in this article focuses on the civilian noninstitutional population, which excludes military servicemembers and individuals in institutions (e.g., prison inmates). ↩︎

- We define the 12-month LFPR of a specified group in any given month to be an unweighted average of monthly labor force participation rates for that group in the most recent 12-month period. For example, the 12-month LFPR for people ages 65-plus in October 2023 is calculated as the unweighted mean of monthly labor force participation rates for the 65-plus population from November 2022 through October 2023. For each group under study, Figure 1 reports the 12-month LFPR at each point in time as a percentage of its value in February 2020. Values above 100 indicate that the 12-month LFPR has risen relative to its February 2020 value, whereas values below 100 indicate that the 12-month LFPR has fallen relative to its February 2020 value. Because our metric focuses on average labor force participation over an entire year, changes in its value are only mildly affected by short-run shocks and do not reflect seasonal variation in labor force participation. Instead, this measure focuses on longer-run shifts in labor supply by each group studied. ↩︎

- Since June 2008, the CPS has tracked disability status with a series of six questions aimed at identifying CPS household members with physical, mental, and/or emotional conditions impacting hearing, vision, cognition (e.g., concentration, memory, decision making), walking/climbing stairs, performing activities outside of the home, or independently completing personal care activities such as bathing. A household member with at least one such condition is counted as having a disability. Additional details are available here. ↩︎

- Because the 12-month LFPR metric is an average of 12 monthly LFPRs, large month-to-month changes will have a limited effect on the 12-month LFPR if those changes are offset in later months. For example, labor force participation among those without disabilities ages 16-64 fell sharply between February and May 2020 but recovered much of that loss over the next few months. ↩︎

- The 12-month LFPR for people ages 16-64 without a disability fell from 77.6 percent in February 2020 to a low of 75.8 percent in March 2021. It is important to emphasize that – even though this decline is only about two percentage points – it translates to a decline in average labor force size of several million people for this group. ↩︎

- Public-use microdata from the Current Population Survey (CPS) identifies people with disabilities dating back to June 2008; as such, 12-month LFPRs for people with and without disabilities can be calculated back to May 2009. ↩︎

- A recent SHRM article provides more details on this subject. ↩︎

- For example, overly inflexible return-to-office (RTO) policies threaten to eliminate productive remote employment opportunities that benefit workers with disabilities and their employers. Risks associated with such RTO policies are examined in a recent Allwork article. Similarly, a recent SHRM article discusses the need for thoughtful RTO policies which allow for hybrid and remote work options that are mutually beneficial to employers and their workers. ↩︎

"

"